Decades of conflict have served to weaken the region’s health system, which has already suffered from chronic under-investment over the years. Many families in Mindanao live in hard-to-reach areas located many miles away from the nearest health centers or public services. Combined with frequent typhoons, earthquakes and flooding – which hit the island annually – communities in Mindanao are considered to be highly vulnerable.

As a native of Mindanao, Joel Taleon, 37, has always known the challenges facing his hometown of Cagayan de Oro. A nursing graduate, Joel recently returned home after working abroad in Japan. He joined Relief International in January 2019 as a Social Mobilizer to encourage parents in his community to vaccinate their children against the poliovirus. Now, he’s using his nursing background to share an urgent message with members of his community: how to protect themselves against the novel coronavirus.

“The last time I went into the community was on April 8,” recalls Joel Taleon, a Social Mobilizer for Relief International’s polio prevention project in Mindanao. “With over 109 million people, the Philippines is usually extremely overcrowded, especially in Mindanao. These days, the streets are completely deserted.”

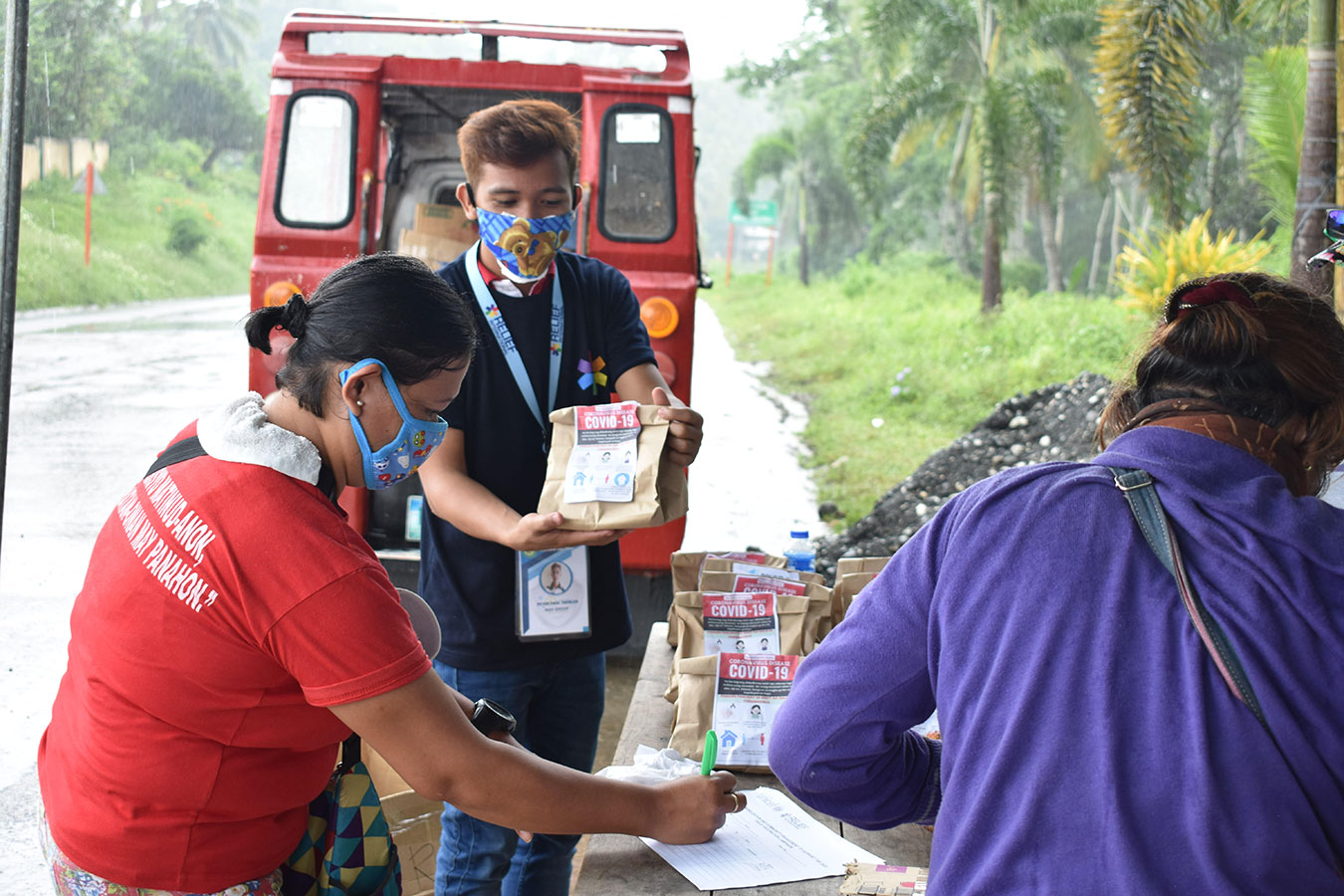

A staff member unloads a box of hygiene supplies for distribution to families at high risk for contracting COVID-19 in Mindanao.

© RI

As of May 2019, the Philippines has surpassed more than 10,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus in, with at least 259 cases reported in Mindanao. The island nation also extended its strict home lockdown and travel restrictions in high risks areas until May 15. It was prompted by rising cases of infection in outbreak hot spots, which include the Mindanao islands.

“We distributed hygiene kits filled with soap, rubbing alcohol, Vitamin C, and any other supplies that we could find in stores to members of the Mindanao community,” shares Joel. The country’s strict lockdowns and other restrictions on movement have made delivering aid more challenging than before. “Even in larger cities, it’s difficult to find any cleaning supplies.”

It wasn’t a normal day at work

The first case of coronavirus in the Philippines was announced on March 7. Few people imagined how rapidly the virus would spread, shutting down businesses, restaurants and schools within a matter of days.

“The last time I went into the community I could see that some members of my team were uncomfortable. It wasn’t a normal day at work,” shares Joel. “I knew I could have already been exposed to COVID-19 and exhibited no symptoms, but even with my nursing background, I was still scared.”

Humanitarian workers responding on the frontlines of this global pandemic are faced with their own fears, anxieties, and increased risk of infecting their own families when they come home after a day of work. But, week after week, our teams continued to show up for work.

“There’s paranoia with every encounter, touch, and conversation. We were very worried but I couldn’t let my fear impact my work.”

“There’s paranoia with every encounter, touch, and conversation. We were very worried but I couldn’t let my fear impact my work.”

Despite this hesitation, Joel remained steadfast in his determination to continue providing humanitarian assistance under the ‘new normal’. Relief International has supported over 45,000 people through the polio campaign program. This includes thousands of families in Mindanao who have received critical hygiene kits as well as information on how to recognize symptoms and to protect themselves against the both unfolding polio and coronavirus outbreaks.

Prior to the pandemic, Relief International focused exclusively on polio prevention by reaching out to parents who had yet to vaccinate their children against the disease. Many families in the Philippines remain fearful of vaccinations after a campaign to inoculate nearly one million schoolchildren against dengue fever in 2016 went awry and jeopardized the health of more than 100,000 people, heightening their risk for severe and sometimes deadly side effects of the vaccine.

In hard-to-reach villages, we conducted large-scale community events for up to 200 people to provide information on the symptoms and treatments for polio. Our teams also used to go door-to-door to meet with parents with children under the age of five who are eligible for the vaccine.

Relief International Social Mobilizers distribute information on polio and COVID-19 outbreaks to families enrolled in our UNICEF-funded Polio Prevention Program in Mindanao.

© RI

Before the outbreak of COVID-19, our teams were able to spend more time with parents to discuss their concerns about inoculating their children against the poliovirus. Now, due to concerns about high transmission rates, we are taking every precaution to keep our staff and the people we serve safe.

“We must respond to both outbreaks because in the areas in which we work, there are more positive cases of polio than COVID-19, at least for now,” shares Joel. “My concern is that if we do not begin to change parents’ perceptions of vaccinations, this could prove extremely dangerous once a vaccine is released to immunize people against the coronavirus.”

Misinformation makes people in vulnerable situations even more vulnerable

In Mindanao, people remain fearful of widespread campaigns to address public health crises, which are sadly all too common here. There are sound reasons for concern that we can – and should – learn from. Most importantly, it’s our job to listen to community members, reduce their fears, and to earn their trust by providing accurate information.

“It’s my job as a social mobilizer, nurse, parent, and a member of this community to provide information about these viruses."

“It’s my job as a social mobilizer, nurse, parent, and a member of this community to provide information about these viruses. The people I speak to can then share what they’ve learned with others. It’s a chain reaction.”

We are continuing to reach out to community members in Mindanao who are at the greatest combined risk for polio and COVID-19. To avoid gathering people in large groups, our teams of local staff members, equipped with masks and gloves to protect themselves, are going house to house to leave fliers for families with information on how to protect themselves against the viruses.

“We limit our time with each family to two minutes in order to prevent the spread of the virus,” shares Joel. “I spend most of the time consoling parents, telling them it’s okay to be worried but not to panic. We all need to remain calm in order to best protect ourselves and our children.”

Still, there is a lot of skepticism in the community. Many people in Mindanao have deep-seeded fears about vaccinations for years ever since the failed dengue fever campaign. We must listen to community members to understand their concerns and dispel any misinformation surrounding the safety of routines vaccines. It may take time for them to accept this information, but parents’ openness to listening to the messages shared by our social mobilizers may be a step forward in changing their mindset.

“I first entered nursing to help members of my community access the healthcare they need to survive. It’s not enough that my own family is safe. I must help protect others in my community against these outbreaks.”